One of the most pivotal roles on any construction project is the one of the main contractor. Their responsibilities shape how buildings perform, how people work together, and ultimately, how safe and successful our projects are. Acting as the central point of coordination, quality control, and on-site execution, main contractors have a unique ability to make or break the flow, compliance, and cohesion of a construction project.

After a site visit Shane and Dean meet at the office:

S: Guess what was missing from site today?

D: Hmm… QA docs, substrate prep, or the will to care?

S: All of the above. Intumescent slapped on like peanut butter. No primer, no DFT, and when I asked for the QA, they showed me a picture of the paint tin.

D: Substrate prep?

S: Dusty steel, sprayed straight over. You could literally see boot prints under the coating. But hey, they used “the right coating.” Like that makes it fire-rated by magic.

D: This is turning into Groundhog Day. That’s the third site this month.

While this is a fictitious conversation, many will find it familiar.

We need to cultivate a culture of response rather than reaction.

In the heat of a project, the default is to react — assign blame, patch the issue, and push on. But these quick fixes often address symptoms, not causes. The problems we frequently firefight on site — compliance failures, coordination breakdowns, cost blowouts — are rarely isolated mistakes. They’re usually signs of deeper systemic and cultural issues embedded in how projects are planned, resourced, and led.

Lets get back to Dean and Shane:

D: Starting to see a pattern here.

S: Yeah — “Apply first, justify later.”

D: And no one’s really trained in the why. It’s treated like paint, not life saving fire protection.

S: Exactly. It’s not just a site issue — it’s baked into how we think about compliance in this country.

D: If people don’t start to understand that the solution lies in shifting our mental model, we’ll keep having this same chat over coffee.

S: Agreed. Next toolbox talk: “DFT is not a vibe, it’s a number.”

If we want to turn problems into learning and create more resilient construction environments, we must learn to examine why our systems allow the same problems to repeat. That means taking a closer look at the underlying dynamics, processes, and mindsets that shape our work culture.

Beneath the surface: Root causes

In the high-pressure world of construction, main contractors are constantly operating within complex systems, navigating tight deadlines, constrained budgets, and a web of interdependencies across trades, consultants, and clients. Delays, cost overruns, compliance failures, and rushed fixes are often seen as just part of the job.

Beneath these surface-level events lie deeper patterns — ones that recur not because people are careless, but because the system is designed (consciously or not) to produce these outcomes. To break this cycle, contractors who look beyond the visible symptoms of failure and engage in seeing problems as part of a deeper structure are more likely to create safe buildings and succeed in the long run.

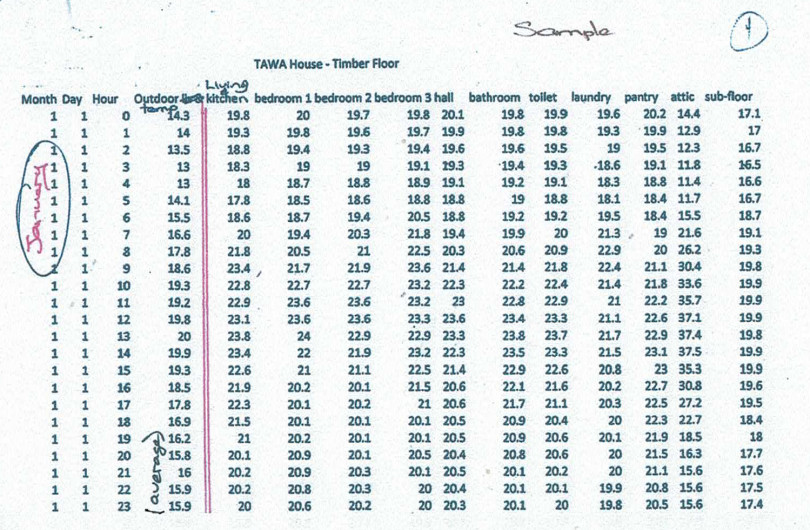

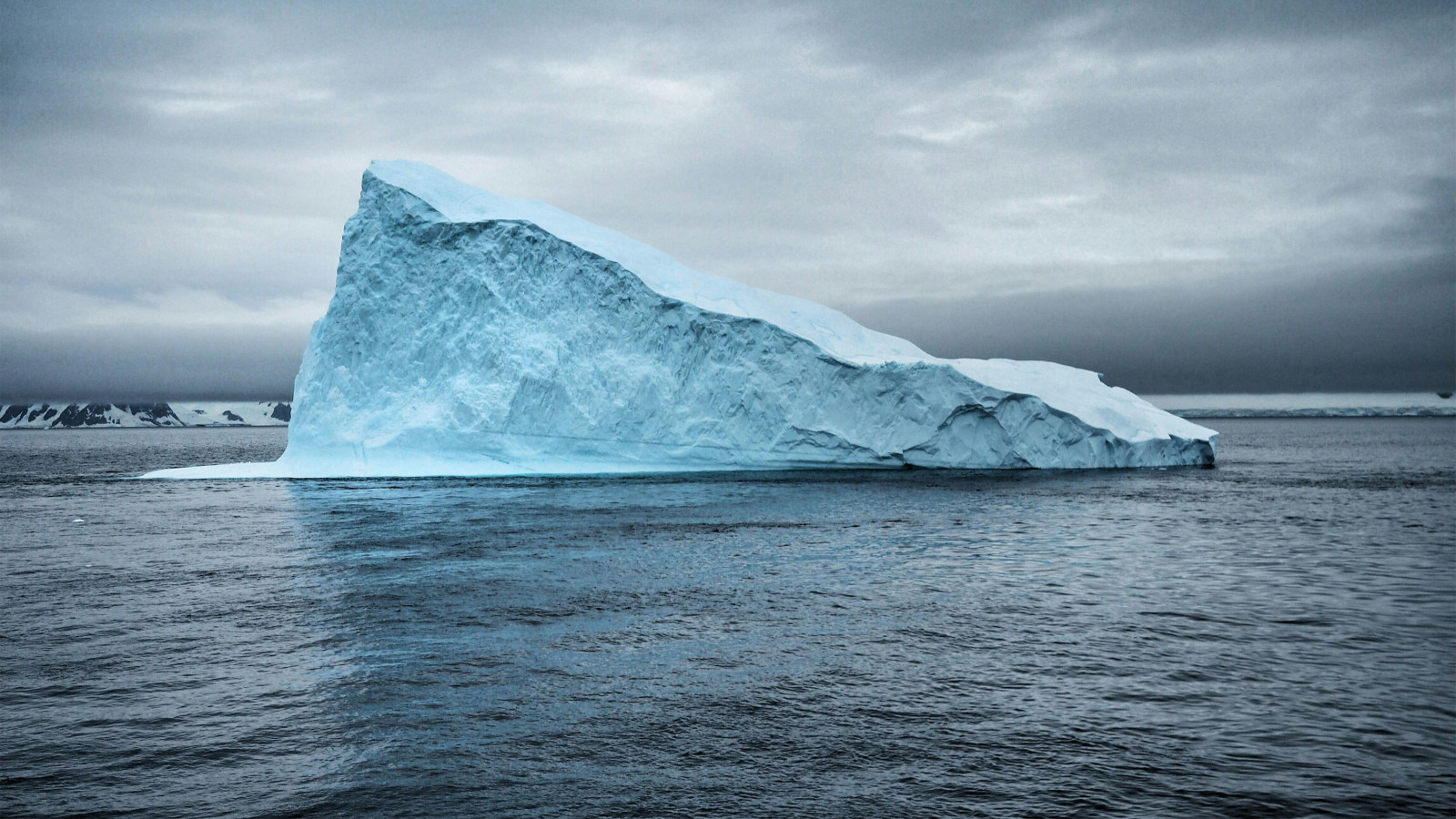

One of the most useful tools in this regard is the Iceberg Model, which helps teams explore the underlying layers beneath any given issue. Applied well, it transforms the way we can understand risk, accountability, and the dynamics of project delivery.

The Iceberg Model

1. Events: What just happened?

At the top of the iceberg are the “events” — the immediate, often disruptive incidents that grab attention and demand a response.

For example, a fire-rated door fails inspection. Plumbing delays prevent a wall from closing. A section of the schedule slips, and the team is suddenly working weekends. These spark reactive decisions, emergency meetings, and often finger pointing.

The default is firefighting; fixing the symptom so the project can move on. While this may be necessary in the short term, it rarely prevents recurrence. We rarely go back to these issues after a project has finished to understand the bigger picture.

Common dynamics:

- Blame and defensiveness —“Who messed this up?”

- Emotional reactivity pushes decision-making into short-term thinking.

- Individuals may avoid taking ownership due to fear of being singled out.

2. Patterns: What’s been happening?

Zooming out, we start to notice recurring issues across multiple projects or stages of the same project. These patterns hint at deeper dysfunction and call for a broader view.

For example, perhaps wall closures are frequently delayed due to unresolved penetrations. Long-lead items like fire doors or cladding may routinely arrive late or mismatched. Site clashes between trades — despite holding regular coordination meetings — might still occur with frustrating frequency.

When we recognise similar events, we move from seeing isolated problems to recognising trends. These trends are often a sign that the system is consistently producing certain outcomes, regardless of individual effort.

Common dynamics:

- Teams become resigned to certain problems: “That always happens.”

- People develop workarounds.

- Fatigue and frustration build, which erodes trust and team cohesion.

3. Systemic Structures: What’s causing the pattern?

Going deeper, we encounter the systemic structures that give rise to these patterns. These include workflows, processes, policies, communication loops, role boundaries, and incentive schemes that operate beneath the surface of day-to-day work.

For example, fire doors may be installed late or incorrectly because procurement deadlines don’t align with coordination, installers lack training, and QA happens too late.

Other common culprits include siloed trade planning and poor integration between design and site. Even without anyone deliberately causing harm, the system is set up to produce consistent friction.

Common dynamics:

- People conform to misaligned processes because “that’s how we do it.”

- Potential avoidance of accountability when structures are vague.

- Power dynamics can prevent people from raising issues early.

4. Mental models: What beliefs keep the system in place?

At the deepest level are the mental models — the assumptions, cultural norms, and beliefs that shape how people think and act. These are rarely spoken aloud, yet they powerfully influence every decision on a project.

A project manager may assume that involving subcontractors early is a waste of time because “they don’t care about design.” A construction team might take shortcuts on compliance because “the certifier will pick it up anyway.”

These mental models become so embedded that they’re invisible. And yet, they shape all the structures above them: how teams communicate, what gets prioritised, and what risks are considered tolerable.

Common dynamics:

- Long-held beliefs act as filters that distort how information is received.

- People protect their identity or professional pride by resisting change.

- Cultural norms like “she’ll be right” reinforce risk tolerance.

Systems thinking is not just an efficiency tool — it’s a legal imperative.

You could argue, "That’s all well and good, but at the end of the day, what I really care about are my legal responsibilities. Why does it matter if my team is reactive or responsive?"

Here’s why: Systems thinking isn't just a tool for smoother workflows, it’s directly tied to legal risk.

The Building Act 2004 governs all construction work in New Zealand. It ensures that buildings are safe, heathy, durable, and compliant with the New Zealand Building Code. While the Act applies to everyone involved in a project, main contractors specifically are accountable for how work is carried out on site:

1. Compliance with the Building Code (Section 17)

All work must meet Building Code standards, whether or not it requires a building consent. This includes:

- Installing passive fire systems exactly as tested and approved

- Matching penetration seals and fire doors to certified details

- Using products per manufacturer guidance (e.g., BRANZ, CodeMark)

Even if an inspector misses a mistake, the main contractor remains liable. That’s why QA systems must be proactive, not reactive.

2. Responsibility for subcontracted work

Delegating work doesn’t delegate legal responsibility. If something fails, courts will hold the main contractor accountable — not the subcontractor.

In this light, systems thinking helps uncover why mistakes happen repeatedly. It reveals structural gaps and cultural blind spots that lead to non-compliance. Ignoring those patterns doesn’t just cause delays; it can expose you to legal consequences.

Therefore, using systems thinking isn't optional or just about being a better manager; it's part of mitigating legal risk and meeting statutory duties.

Conclusion

Unless a team takes time to address all the layers of the iceberg — events, patterns, structures, and mental models — the same problems will resurface in new forms. Shifting from reactive firefighting to strategic, systems-informed responses is not only more effective, it’s also legally safer.

Construction doesn’t have to be a cycle of repeated mistakes and strained relationships. By adopting systems thinking, (not only) main contractors can:

- Lead with curiosity instead of blame.

- Build structures that align accountability with capability.

- Support a culture that speaks up early and learns continuously.

- Move beyond tick-box compliance toward integrated care and responsibility.

Because when it comes to quality and compliance, what you don’t see can hurt you — legally, structurally, and relationally.

Most Popular

Most Popular Popular Products

Popular Products